As an archivist, I was, and still am, fascinated with how people are remembered in the future. A few years ago, I had the unique privilege of working with a large mass of personal & professional papers from a single influential family in a small town. Their ancestors had lived in the same house for over 140 years and their attic was a proverbial treasure trove. They didn’t throw away anything that pertained to themselves – they just stashed it upstairs! I discovered the intricacies of relationships, like a play unfolding before me in the scraps of silverfish nibbled paper. Local historians know their cast of characters but we often do not understand how they behaved towards each other or what they liked to eat. Finding these tidbits of memories was like panning for gold in the dusty boxes from an antebellum brick house on Main Street.

As an archivist, I was, and still am, fascinated with how people are remembered in the future. A few years ago, I had the unique privilege of working with a large mass of personal & professional papers from a single influential family in a small town. Their ancestors had lived in the same house for over 140 years and their attic was a proverbial treasure trove. They didn’t throw away anything that pertained to themselves – they just stashed it upstairs! I discovered the intricacies of relationships, like a play unfolding before me in the scraps of silverfish nibbled paper. Local historians know their cast of characters but we often do not understand how they behaved towards each other or what they liked to eat. Finding these tidbits of memories was like panning for gold in the dusty boxes from an antebellum brick house on Main Street.

Through the endless sorting of papers, I was able to piece together the life of a young woman, who died at age 29, a person whom we only knew from her name and two dates on a headstone in the family plot. She had a full life – was able to attend a finishing school for ladies in the 1870’s, taught in local grade schools, enjoyed reading the classics and current literature, and went on excursions with her friends. Along with her letters and essay books, the family donated a trunk of clothing, the unpacking of which was a somber but thrilling chore for a material culture historian. In the trunk were the black and grey shaded accouterments of Victorian mourning garb from 1882, the year Miss Emma died. The expense shown in the jet buttons, the parasol, the silk shawls, the custom dresses, was a visible sign to the world of how bereaved the family felt at her loss.

When handling her personal effects, I often reflected on the nature of the survival of memory, of whether Miss Emma had any idea the contents of her writing box would be read three generations later. The remarkable gift of love and stability – or some may argue – a lazy neglect from her future relations gave us a peek into a rare story, an ordinary life. Ordinariness is easily lost. Peasant linen clothing was worn to shreds and then eventually turned into paper. Wooden houses burn down. Small traditions die out with families. The real struggle for social historians is finding the examples and explanations for why a thing or an image exists. We have to accept some questions may never be answered.

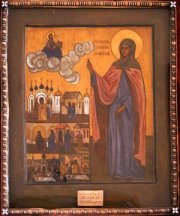

When teaching the girls in my parish about women saints, I wanted to include an ‘every day’ saint – one who, from outward appearances, was ordinary to her time and place, but lived a holy life nonetheless. When I read about St. Juliana of Lazarevo, I found a saint, who, but for the loving attention of her son, would be unknown to us today. She was a pious soul from early childhood, being orphaned and left with relatives who did not understand her ways, she kept a practical faith. She cared for the sick and sewed clothing and burial shrouds for the poor. A fellow nobleman fell in love with her and brought her into his parents’ household. Juliana quickly showed her skill in managing a burgeoning home, having given birth to ten sons and three daughters. Her in-laws turned over the keys to her for the estate.

Juliana suffered deep sorrow when six of her children died from plague. Her desire was to retire from the world to the monastery. Her husband, Yuri, encouraged her to stay with the family and see their remaining children grow into adulthood. So, Juliana stayed at Murom and re-doubled her ascetic efforts. After her husband died, Juliana did not go to a monastery but decided to stay in the world, living in poverty because she gave away her inheritance to the poor. Even during famine, she made sure to have bread to give to beggars which was, “sweeter than anything they had ever tasted.” Several years after her death, Juliana’s relics were found incorrupt and streamed myrrh that brought healing to many.

There are several themes I could have taught from St. Juliana’s life – her practical holiness, her obedience to the path of salvation within marriage & family life, her charitableness from a position of inherited wealth – all of which are foundational lessons. What I found most fascinating is the gift of remembrance St. Juliana received within the life of the Church as an otherwise unremarkable woman in her time and place. Her son, George, praised her in writing, which, at the time in early 17th century Russia, was a rare task and this writing was preserved after his death, providentially, at the time his mother’s relics were found incorrupt.

For Orthodox Christians, remembrance is the task of the living. I heard it said, that even in the darkest times of the Communist era, when no service books survived in a town, priests could rely on the grandmothers to know the liturgical prayers by heart. We have a vast family ‘attic’ of written collections in a hundred languages of saint’s lives and the liturgical functions of the Church. The akathists teach us through rhythm and song the lives of the saints. In most countries where Orthodoxy has grown, the majority of people are literate and can have access to all these materials in their native language. While the printed word ‘outsources’ memory to a certain extent, it has never replaced the inherent nature of our faith tradition, that which is taught by example, what is sung by the elders and repeated by the young. Paper, vellum, and stone are trustworthy to an extent, but only so far as the people who value them. Living in the Church of the martyrs, we know all too dearly how quickly the elements burn. Our strength in Christ is our collective memories, to keep the Word alive in speech and deed, that no man or element can destroy.

Links:

https://orthodoxwiki.org/Juliana_of_Lazarevo

https://stjulianalazarevo.org/the_saints_life.html

What makes for an influential life? Why do you listen to certain people and not others? What sort of human qualities do you admire? These questions have occupied philosophers and religious people for all of civilization. How we define social power, outside of the brute strength of the sword, depends a great deal on when and where we live. There are a few universals: wealth, birth, physical appearance, sex, and character are the five main determinations of influence. For most societies, who your parents were and how much money or property you inherited delimited your social circle and how you could operate in that circle.

What makes for an influential life? Why do you listen to certain people and not others? What sort of human qualities do you admire? These questions have occupied philosophers and religious people for all of civilization. How we define social power, outside of the brute strength of the sword, depends a great deal on when and where we live. There are a few universals: wealth, birth, physical appearance, sex, and character are the five main determinations of influence. For most societies, who your parents were and how much money or property you inherited delimited your social circle and how you could operate in that circle.